Byzantine music (

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

: Βυζαντινή μουσική) is the music of the

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

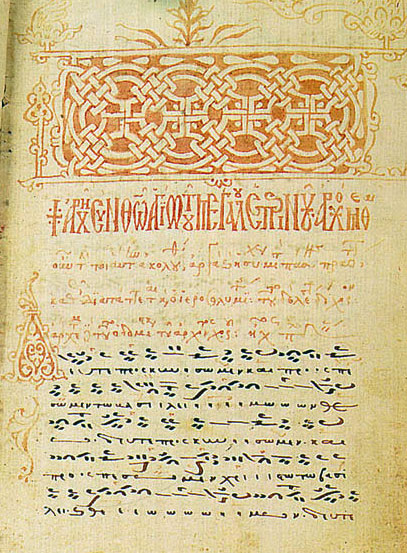

. Originally it consisted of songs and hymns composed to Greek texts used for courtly ceremonials, during festivals, or as paraliturgical and liturgical music. The ecclesiastical forms of Byzantine music are the best known forms today, because different Orthodox traditions still identify with the heritage of Byzantine music, when their cantors sing monodic chant out of the traditional chant books such as the

Sticherarion

A sticheron (Greek: "set in verses"; plural: stichera; Greek: ) is a hymn of a particular genre sung during the daily evening (Hesperinos/Vespers) and morning (Orthros) offices, and some other services, of the Eastern Orthodox and Byzantine Cath ...

, which in fact consisted of five books, and the

Irmologion

Irmologion ( grc-gre, τὸ εἱρμολόγιον ) is a liturgical book of the Eastern Orthodox Church and those Eastern Catholic Churches which follow the Byzantine Rite. It contains ''irmoi'' () organised in sequences of odes (, sg. ) an ...

.

Byzantine music did not disappear after the

fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city fell on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 53-day siege which had begun o ...

. Its traditions continued under the

Patriarch of Constantinople

The ecumenical patriarch ( el, Οἰκουμενικός Πατριάρχης, translit=Oikoumenikós Patriárchēs) is the archbishop of Constantinople (Istanbul), New Rome and '' primus inter pares'' (first among equals) among the heads of th ...

, who after the Ottoman conquest in 1453 was granted

administrative responsibilities over all

Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first millennium, the mainstream (or "canonical") ...

Christians in the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. During the decline of the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century, burgeoning splinter nations in the Balkans declared

autonomy

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy, from , ''autonomos'', from αὐτο- ''auto-'' "self" and νόμος ''nomos'', "law", hence when combined understood to mean "one who gives oneself one's ...

or

autocephaly

Autocephaly (; from el, αὐτοκεφαλία, meaning "property of being self-headed") is the status of a hierarchical Christian church whose head bishop does not report to any higher-ranking bishop. The term is primarily used in Eastern O ...

from the Patriarchate of Constantinople. The new self-declared patriarchates were independent nations defined by their religion.

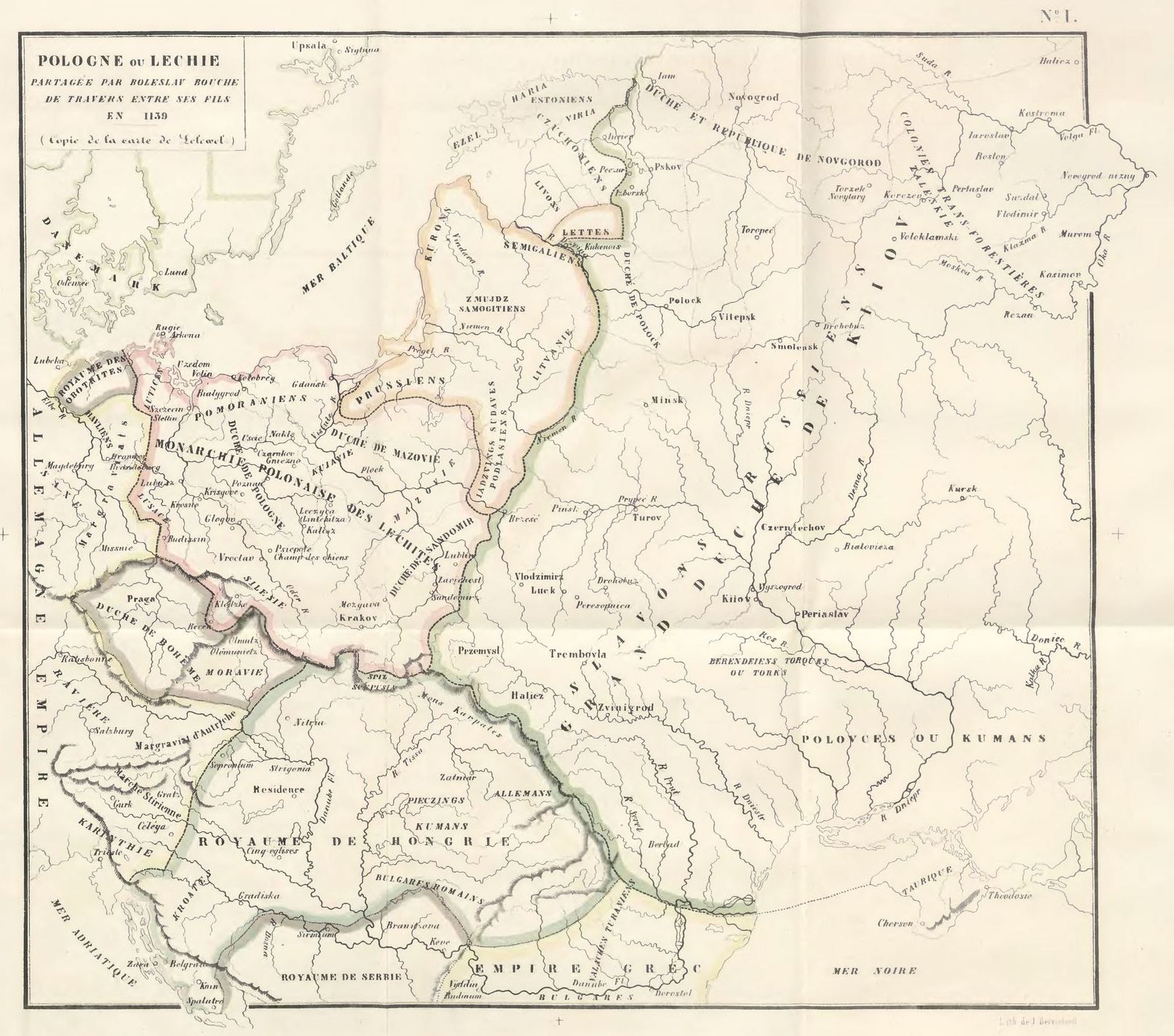

In this context, Christian religious chant practiced in the Ottoman Empire, in, among other nations,

Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

,

Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe, Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Bas ...

and

Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

, was based on the historical roots of the art tracing back to the Byzantine Empire, while the music of the Patriarchate created during the

Ottoman period was often regarded as "post-Byzantine". This explains why Byzantine music refers to several Orthodox Christian chant traditions of the Mediterranean and of the Caucasus practiced in recent history and even today, and this article cannot be limited to the music culture of the Byzantine past.

The Byzantine chant was added by

UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

in 2019 to its list of

Intangible Cultural Heritage

An intangible cultural heritage (ICH) is a practice, representation, expression, knowledge, or skill considered by UNESCO to be part of a place's cultural heritage. Buildings, historic places, monuments, and artifacts are cultural property. Int ...

"as a living art that has existed for more than 2000 years, the Byzantine chant is a significant cultural tradition and comprehensive music system forming part of the common musical traditions that developed in the Byzantine Empire".

Imperial age

The tradition of eastern liturgical chant, encompassing the

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

-speaking world, developed even before the establishment of the new Roman capital,

Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, in 330 until

its fall in 1453. Byzantine music was influenced by Hellenistic music traditions, classic Greek music as well as religious music traditions of Syriac and Hebrew cultures. The Byzantine system of

octoechos

Oktōēchos (here transcribed "Octoechos"; Greek: ;The feminine form exists as well, but means the book octoechos. from ὀκτώ "eight" and ἦχος "sound, mode" called echos; Slavonic: Осмогласие, ''Osmoglasie'' from о́с� ...

, in which melodies were classified into eight modes, is specifically thought to have been exported from Syria, where it was known in the 6th century, before its legendary creation by

John of Damascus. It was imitated by musicians of the 7th century to create Arab music as a synthesis of Byzantine and Persian music, and these exchanges were continued through the Ottoman Empire until Istanbul today.

The term Byzantine music is sometimes associated with the medieval sacred chant of

Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

Churches following the

Constantinopolitan Rite

The Byzantine Rite, also known as the Greek Rite or the Rite of Constantinople, identifies the wide range of cultural, liturgical, and canonical practices that developed in the Eastern Christian Church of Constantinople.

The canonical hours are ...

. There is also an identification of "Byzantine music" with "Eastern Christian liturgical chant", which is due to certain monastic reforms, such as the Octoechos reform of the

Quinisext Council

The Quinisext Council (Latin: ''Concilium Quinisextum''; Koine Greek: , ''Penthékti Sýnodos''), i.e. the Fifth-Sixth Council, often called the Council ''in Trullo'', Trullan Council, or the Penthekte Synod, was a church council held in 692 at ...

(692) and the later reforms of the

Stoudios Monastery under its abbots

Sabas Sabas is a name derived from the Greek Savvas or Sabbas.

Sabas may refer to, chronologically:

Given name

* Abda and Sabas, two early Christian martyrs and saints whose vitas are lost

* Julian Sabas (died 377), hermit who spent most of his life i ...

and

Theodore

Theodore may refer to:

Places

* Theodore, Alabama, United States

* Theodore, Australian Capital Territory

* Theodore, Queensland, a town in the Shire of Banana, Australia

* Theodore, Saskatchewan, Canada

* Theodore Reservoir, a lake in Sask ...

. The

triodion

The Triodion ( el, Τριῴδιον, ; cu, Постнаѧ Трїωдь, ; ro, Triodul, sq, Triod/Triodi), also called the Lenten Triodion (, ), is a liturgical book used by the Eastern Orthodox Church. The book contains the propers for th ...

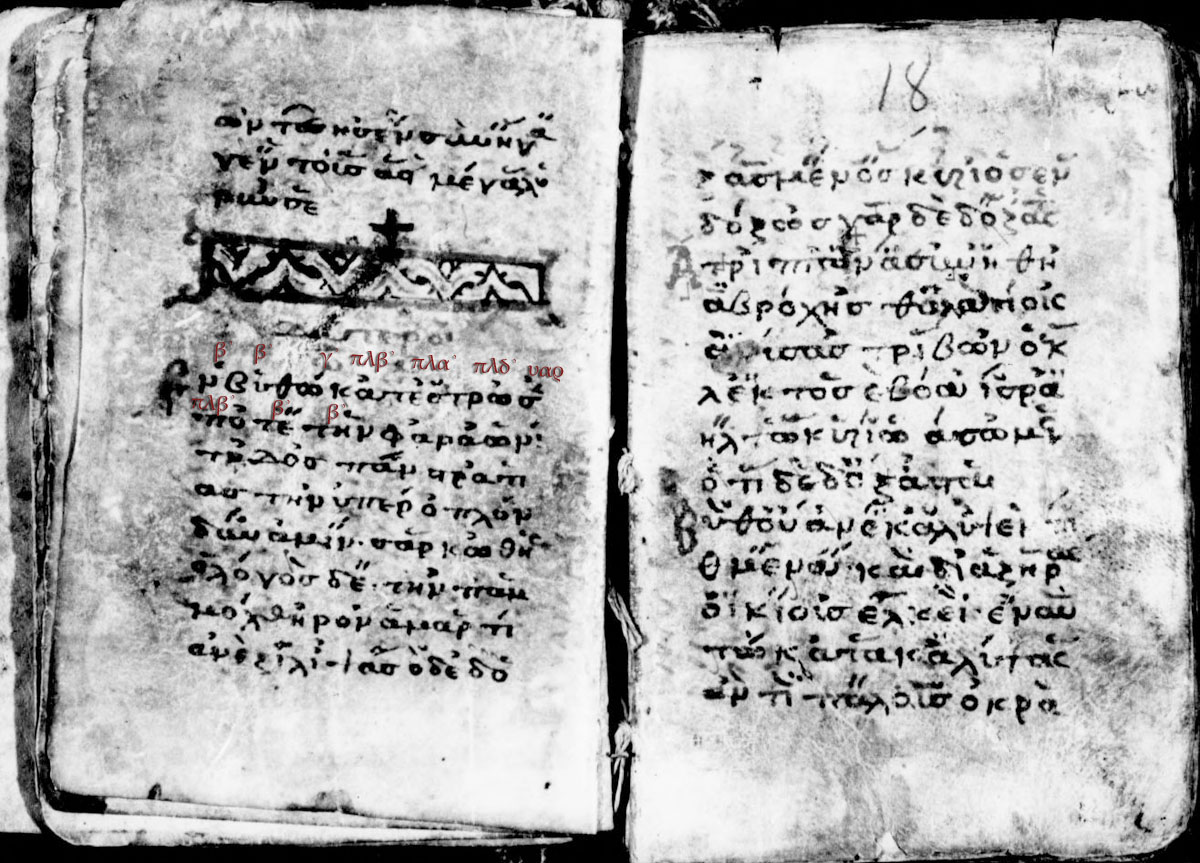

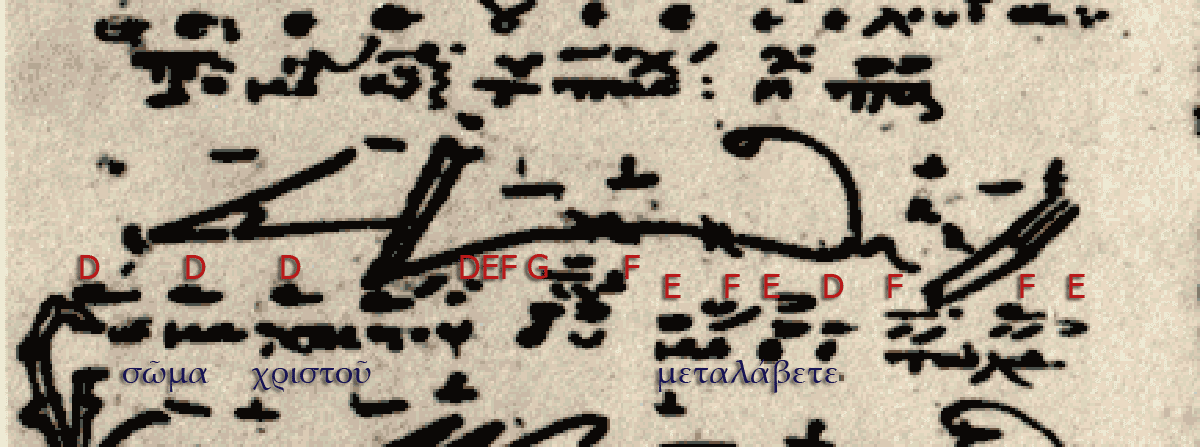

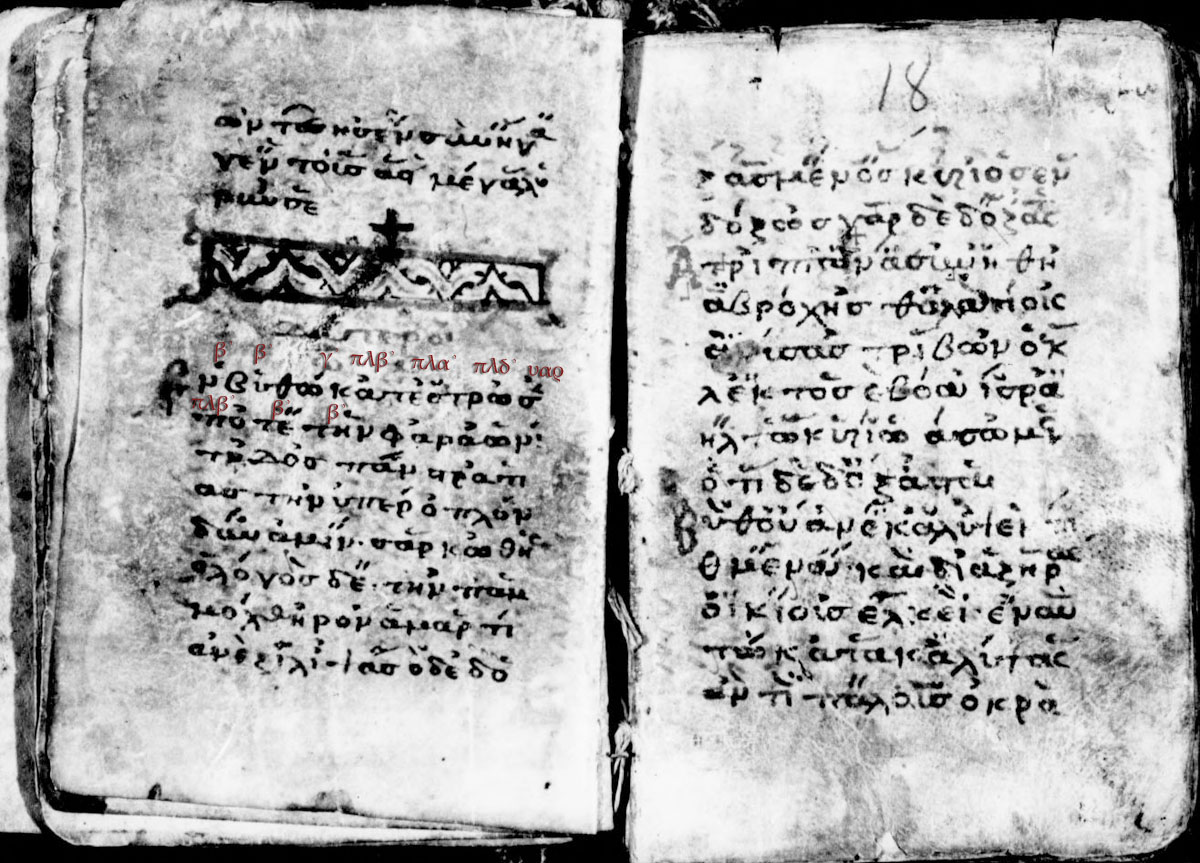

created during the reform of Theodore was also soon translated into Slavonic, which required also the adaption of melodic models to the prosody of the language. Later, after the Patriarchate and Court had returned to Constantinople in 1261, the former cathedral rite was not continued, but replaced by a mixed rite, which used the Byzantine Round notation to integrate the former notations of the former chant books (

Papadike). This notation had developed within the book

sticherarion

A sticheron (Greek: "set in verses"; plural: stichera; Greek: ) is a hymn of a particular genre sung during the daily evening (Hesperinos/Vespers) and morning (Orthros) offices, and some other services, of the Eastern Orthodox and Byzantine Cath ...

created by the Stoudios Monastery, but it was used for the books of the cathedral rites written in a period after the

fourth crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

, when the cathedral rite was already abandoned at Constantinople. It is being discussed that in the Narthex of the Hagia Sophia an organ was placed for use in secular processions of the Emperor's entourage.

The earliest sources and the tonal system of Byzantine music

According to the chant manual "

Hagiopolites" of 16 church tones (

echoi), the author of this treatise introduces a tonal system of 10 echoi. Nevertheless, both schools have in common a

set of 4 octaves (', and '), each of them had a ' (

authentic mode

A Gregorian mode (or church mode) is one of the eight systems of pitch organization used in Gregorian chant.

History

The name of Pope Gregory I was attached to the variety of chant that was to become the dominant variety in medieval western and ...

) with the finalis on the degree V of the mode, and a ' (

plagal mode

A Gregorian mode (or church mode) is one of the eight systems of pitch organization used in Gregorian chant.

History

The name of Pope Gregory I was attached to the variety of chant that was to become the dominant variety in medieval western and ...

) with the final note on the degree I. According to Latin theory, the resulting eight tones (

octoechos

Oktōēchos (here transcribed "Octoechos"; Greek: ;The feminine form exists as well, but means the book octoechos. from ὀκτώ "eight" and ἦχος "sound, mode" called echos; Slavonic: Осмогласие, ''Osmoglasie'' from о́с� ...

) had been identified with the seven modes (octave species) and tropes (

tropoi which meant the transposition of these modes). The names of the tropes like "Dorian" etc. had been also used in Greek chant manuals, but the names Lydian and Phrygian for the octaves of and had been sometimes exchanged. The Ancient Greek

''harmonikai'' was a Hellenist reception of the

Pythagorean

Pythagorean, meaning of or pertaining to the ancient Ionian mathematician, philosopher, and music theorist Pythagoras, may refer to:

Philosophy

* Pythagoreanism, the esoteric and metaphysical beliefs purported to have been held by Pythagoras

* Ne ...

education programme defined as mathemata ("exercises"). Harmonikai was one of them. Today, chanters of the Christian Orthodox churches identify with the heritage of Byzantine music whose earliest composers are remembered by name since the 5th century. Compositions had been related to them, but they must be reconstructed by notated sources which date centuries later. The melodic neume notation of Byzantine music developed late since the 10th century, with the exception of an earlier

ekphonetic notation, interpunction signs used in

lectionaries

A lectionary ( la, lectionarium) is a book or listing that contains a collection of scripture readings appointed for Christian or Judaic worship on a given day or occasion. There are sub-types such as a "gospel lectionary" or evangeliary, and a ...

, but modal signatures for the eight echoi can already be found in fragments (

papyri

Papyrus ( ) is a material similar to thick paper that was used in ancient times as a writing surface. It was made from the pith of the papyrus plant, ''Cyperus papyrus'', a wetland sedge. ''Papyrus'' (plural: ''papyri'') can also refer to a d ...

) of monastic hymn books (tropologia) dating back to the 6th century.

Amid the rise of

Christian civilization

Christianity has been intricately intertwined with the history and formation of Western society. Throughout its long history, the Church has been a major source of social services like schooling and medical care; an inspiration for art, cult ...

within Hellenism, many concepts of knowledge and education survived during the imperial age, when Christianity became the official religion. The

Pythagorean sect and music as part of the four "cyclical exercises" (ἐγκύκλια μαθήματα) that preceded the Latin quadrivium and science today based on mathematics, established mainly among Greeks in southern Italy (at

Taranto

Taranto (, also ; ; nap, label= Tarantino, Tarde; Latin: Tarentum; Old Italian: ''Tarento''; Ancient Greek: Τάρᾱς) is a coastal city in Apulia, Southern Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Taranto, serving as an important com ...

and

Crotone

Crotone (, ; nap, label= Crotonese, Cutrone or ) is a city and ''comune'' in Calabria, Italy. Founded as the Achaean colony of Kroton ( grc, Κρότων or ; la, Crotona) in Magna Graecia, it was known as Cotrone from the Middle Ages until ...

). Greek anachoretes of the early Middle Ages did still follow this education. The Calabrian

Cassiodorus

Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator (c. 485 – c. 585), commonly known as Cassiodorus (), was a Roman statesman, renowned scholar of antiquity, and writer serving in the administration of Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths. ''Senator'' w ...

founded Vivarium where he translated Greek texts (science, theology and the Bible), and

John of Damascus who learnt Greek from a Calabrian monk Kosmas, a slave in the household of his privileged father at Damascus, mentioned mathematics as part of the speculative philosophy.

According to him philosophy was divided into theory (theology, physics, mathematics) and practice (ethics, economy, politics), and the Pythagorean heritage was part of the former, while only the ethic effects of music were relevant in practice. The mathematic science ''harmonics'' was usually not mixed with the concrete topics of a chant manual.

Nevertheless, Byzantine music is modal and entirely dependent on the Ancient Greek concept of harmonics. Its tonal system is based on a synthesis with

ancient Greek models, but we have no sources left that explain to us how this synthesis was done.

Carolingian

The Carolingian dynasty (; known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings, Karolinger or Karlings) was a Frankish noble family named after Charlemagne, grandson of mayor Charles Martel and a descendant of the Arnulfing and Pippin ...

cantors could mix the science of harmonics with a discussion of church tones, named after the ethnic names of the octave species and their transposition tropes, because they invented their own octoechos on the basis of the Byzantine one. But they made no use of earlier Pythagorean concepts that had been fundamental for Byzantine music, including:

It is not evident by the sources, when exactly the position of the minor or half tone moved between the and . It seems that the fixed degrees (hestotes) became part of a new concept of the echos as melodic

mode

Mode ( la, modus meaning "manner, tune, measure, due measure, rhythm, melody") may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* '' MO''D''E (magazine)'', a defunct U.S. women's fashion magazine

* ''Mode'' magazine, a fictional fashion magazine which is ...

(not simply

octave species

In the musical system of ancient Greece, an octave species (εἶδος τοῦ διὰ πασῶν, or σχῆμα τοῦ διὰ πασῶν) is a specific sequence of intervals within an octave. In '' Elementa harmonica'', Aristoxenus classi ...

), after the echoi had been called by the ethnic names of the tropes.

Instruments within the Byzantine Empire

The 9th century

Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

geographer

Ibn Khurradadhbih (d. 911); in his lexicographical discussion of instruments cited the

lyra

Lyra (; Latin for lyre, from Greek ''λύρα'') is a small constellation. It is one of the 48 listed by the 2nd century astronomer Ptolemy, and is one of the modern 88 constellations recognized by the International Astronomical Union. Lyra wa ...

(lūrā) as the typical instrument of the Byzantines along with the ''urghun'' (

organ), ''shilyani'' (probably a type of

harp

The harp is a stringed musical instrument that has a number of individual strings running at an angle to its soundboard; the strings are plucked with the fingers. Harps can be made and played in various ways, standing or sitting, and in orche ...

or

lyre

The lyre () is a stringed musical instrument that is classified by Hornbostel–Sachs as a member of the lute-family of instruments. In organology, a lyre is considered a yoke lute, since it is a lute in which the strings are attached to a yoke ...

) and the ''salandj'' (probably a

bagpipe

Bagpipes are a woodwind instrument using enclosed reeds fed from a constant reservoir of air in the form of a bag. The Great Highland bagpipes are well known, but people have played bagpipes for centuries throughout large parts of Europe, Nor ...

).

[.]

The first of these, the early bowed stringed instrument known as the

Byzantine lyra

The Byzantine lyra or lira ( gr, λύρα) was a medieval bowed string musical instrument in the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire. In its popular form, the lyra was a pear-shaped instrument with three to five strings, held upright and played by ...

, would come to be called the ''

lira da braccio

The lira da braccio (or ''lyra de bracio''Michael Praetorius. Syntagma Musicum Theatrum Instrumentorum seu Sciagraphia Wolfenbüttel 1620) was a European bowed string instrument of the Renaissance. It was used by Italian poet-musicians in court i ...

'', in Venice, where it is considered by many to have been the predecessor of the contemporary violin, which later flourished there.

The bowed "lyra" is still played in former Byzantine regions, where it is known as the

Politiki lyra (lit. "lyra of the City" i.e.

Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

) in Greece, the

Calabrian lira

The Calabrian lira ( it, lira Calabrese) is a traditional musical instrument characteristic of some areas of Calabria, region in southern Italy.

Characteristics

The lira of Calabria is a bowed string instrument with three strings. Like most bo ...

in Southern Italy, and the

Lijerica

)

* Gudok (''russian: гудок'' '' uk, гудок'')

* Kemenche

* Rabel (instrument)

* Rabāb (Arabic الرباب)

* Rebec

* violin

The lijerica () is a musical instrument from the Croatian region of Dalmatia and Croatian parts of eastern H ...

in

Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

.

The second instrument, the

Hydraulis

The water organ or hydraulic organ ( el, ὕδραυλις) (early types are sometimes called hydraulos, hydraulus or hydraula) is a type of pipe organ blown by air, where the power source pushing the air is derived by water from a natural source ...

, originated in the

Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

world and was used in the

Hippodrome

The hippodrome ( el, ἱππόδρομος) was an ancient Greek stadium for horse racing and chariot racing. The name is derived from the Greek words ''hippos'' (ἵππος; "horse") and ''dromos'' (δρόμος; "course"). The term is used i ...

in Constantinople during races.

A

pipe organ

The pipe organ is a musical instrument that produces sound by driving pressurized air (called ''wind'') through the organ pipes selected from a keyboard. Because each pipe produces a single pitch, the pipes are provided in sets called ''ranks ...

with "great leaden pipes" was sent by the emperor

Constantine V

Constantine V ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντῖνος, Kōnstantīnos; la, Constantinus; July 718 – 14 September 775), was Byzantine emperor from 741 to 775. His reign saw a consolidation of Byzantine security from external threats. As an able ...

to

Pepin the Short

the Short (french: Pépin le Bref; – 24 September 768), also called the Younger (german: Pippin der Jüngere), was King of the Franks from 751 until his death in 768. He was the first Carolingian to become king.

The younger was the son of ...

King of the

Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools, ...

in 757. Pepin's son

Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy ...

requested a similar organ for his chapel in

Aachen

Aachen ( ; ; Aachen dialect: ''Oche'' ; French and traditional English: Aix-la-Chapelle; or ''Aquisgranum''; nl, Aken ; Polish: Akwizgran) is, with around 249,000 inhabitants, the 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the 28th- ...

in 812, beginning its establishment in Western church music.

[ Despite this, the Byzantines never used pipe organs and kept the flute-sounding Hydraulis until the ]Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

.

The final Byzantine instrument, the aulos

An ''aulos'' ( grc, αὐλός, plural , ''auloi'') or ''tibia'' (Latin) was an ancient Greek wind instrument, depicted often in art and also attested by archaeology.

Though ''aulos'' is often translated as "flute" or "double flute", it was usu ...

, was a double-reeded woodwind like the modern oboe

The oboe ( ) is a type of double reed woodwind instrument. Oboes are usually made of wood, but may also be made of synthetic materials, such as plastic, resin, or hybrid composites. The most common oboe plays in the treble or soprano range.

A ...

or Armenian duduk

The duduk ( ; hy, դուդուկ ) or tsiranapogh ( hy, ծիրանափող, meaning “apricot-made wind instrument”), is an ancient Armenian double reed woodwind instrument made of apricot wood. It is indigenous to Armenia. Variations of th ...

. Other forms include the ''plagiaulos'' (πλαγίαυλος, from πλάγιος, ''plagios'' "sideways"), which resembled the flute

The flute is a family of classical music instrument in the woodwind group. Like all woodwinds, flutes are aerophones, meaning they make sound by vibrating a column of air. However, unlike woodwind instruments with reeds, a flute is a reedless ...

,wine-skin

A wineskin is an ancient type of bottle made of leathered animal skin, usually from goats or sheep, used to store or transport wine.

History

Its first mentions come from Ancient Greece, where, in the parties called Bacchanalia, dedicated to t ...

"), a bagpipe.[William Flood. ''The Story of the Bagpipe'' p. 15](_blank)

/ref> These bagpipes, also known as ''Dankiyo

Dankiyo (from ancient Greek: To angeion (Τὸ ἀγγεῖον)), is an ancient word from the text of Evliya Çelebi (17th century, Ottoman Era "The Laz's of Trebizond invented a bagpipe called a dankiyo..."ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

: To angeion (Τὸ ἀγγεῖον) "the container"), had been played even in Roman times. Dio Chrysostom

Dio Chrysostom (; el, Δίων Χρυσόστομος ''Dion Chrysostomos''), Dion of Prusa or Cocceianus Dio (c. 40 – c. 115 AD), was a Greek orator, writer, philosopher and historian of the Roman Empire in the 1st century AD. Eighty of his ...

wrote in the 1st century of a contemporary sovereign (possibly Nero) who could play a pipe (tibia

The tibia (; ), also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates (the other being the fibula, behind and to the outside of the tibia); it connects ...

, Roman reedpipes similar to Greek aulos) with his mouth as well as by tucking a bladder beneath his armpit. The bagpipes continued to be played throughout the empire's former realms down to the present. (See Balkan Gaida

A gaida is a bagpipe from Southeastern Europe. Southern European bagpipes known as ''gaida'' include: the , , (), () () or (), ''(')'', , also .

Construction

Bag

Gaida bags are generally of sheep or goat hide. Different regions have ...

, Greek Tsampouna

The tsampouna (or tsambouna; el, τσαμπούνα) is a Greek musical instrument and part of the bagpipe family. It is a double- chantered bagpipe, with no drone, and is inflated by blowing by mouth into a goatskin bag. The instrument is wides ...

, Pontic

Pontic, from the Greek ''pontos'' (, ), or "sea", may refer to:

The Black Sea Places

* The Pontic colonies, on its northern shores

* Pontus (region), a region on its southern shores

* The Pontic–Caspian steppe, steppelands stretching from no ...

Tulum

Tulum (, yua, Tulu'um) is the site of a pre-Columbian Mayan walled city which served as a major port for Coba, in the Mexican state of Quintana Roo. The ruins are situated on cliffs along the east coast of the Yucatán Peninsula on the Caribb ...

, Cretan Askomandoura

Askomandoura ( el, ασκομαντούρα) is a type of bagpipe played as a traditional instrument on the Greek island of Crete, similar to the '' tsampouna''.

Its use in Crete is attested in illustrations from the mid-15th Century.Ioannis Tsouc ...

, Armenian Parkapzuk The ''parkapzuk'' ( hy, Պարկապզուկ) is a droneless, horn-belled bagpipe played in Armenia. The double-chanters each have five or six finger-holes, but the chanters are tuned slightly apart, giving a " beat" as the soundwaves of each inte ...

, Zurna

The zurna (Armenian language, Armenian: զուռնա zuṙna; Classical Armenian, Old Armenian: սուռնայ suṙnay; Albanian language, Albanian: surle/surla; Persian language, Persian: karna/Kornay/surnay; Macedonian language, Macedonian: з ...

and Romanian Cimpoi

Cimpoi is the Romanian bagpipe.

Cimpoi has a single drone called '' bâzoi'' or ''bîzoi'' ("buzzer") and straight bore chanter called '' carabă'' ("whistle"). It is less strident than its Balkan relatives.

The chanter often has five to ei ...

.)

Other commonly used instruments used in Byzantine Music include the Kanonaki

The qanun, kanun, ganoun or kanoon ( ar, قانون, qānūn; hy, քանոն, k’anon; ckb, قانون, qānūn; el, κανονάκι, kanonáki; he, קָאנוּן, ''qanun''; fa, , ''qānūn''; tr, kanun; az, qanun; ) is a string ...

, Oud

, image=File:oud2.jpg

, image_capt=Syrian oud made by Abdo Nahat in 1921

, background=

, classification=

* String instruments

*Necked bowl lutes

, hornbostel_sachs=321.321-6

, hornbostel_sachs_desc=Composite chordophone sounded with a plectrum

, ...

, Laouto

The laouto ( el, λαούτο, pl. laouta ) is a long-neck fretted instrument of the lute family, found in Greece and Cyprus, and similar in appearance to the oud. It has four double-strings. It is played in most respects like the oud (plucked ...

, Santouri

The santur (also ''santūr'', ''santour'', ''santoor'') ( fa, سنتور), is a hammered dulcimer of Iranian origins.--- Rashid, Subhi Anwar (1989). ''Al-ʼĀlāt al-musīqīyya al-muṣāhiba lil-Maqām al-ʻIrāqī''. Baghdad: Matbaʻat al-ʻ ...

, Toubeleki

The toubeleki ( el, τουμπελέκι and τουμπερλέκι and ντουμπελέκι), is a kind of a Greek traditional drum musical instrument. It is usually made from metal, open at its downside and covered with a skin stretched over i ...

, Tambouras

The tambouras ( el, ταμπουράς ) is a Greek traditional string instrument of Byzantine origin. It has existed since at least the 10th century, when it was known in Assyria and Egypt. At that time, it might have between two and six strings ...

, Defi Tambourine, Çifteli

The çifteli (çiftelia, qifteli or qyfteli , sq, "doubled" or "double stringed") is a plucked string instrument, with only two strings, played mainly by the Albanians of northern and central Albania, Southern Montenegro, parts of North Maced ...

(which was known as Tamburica in Byzantine times), Lyre

The lyre () is a stringed musical instrument that is classified by Hornbostel–Sachs as a member of the lute-family of instruments. In organology, a lyre is considered a yoke lute, since it is a lute in which the strings are attached to a yoke ...

, Kithara, Psaltery

A psaltery ( el, ψαλτήρι) (or sawtry, an archaic form) is a fretboard-less box zither (a simple chordophone) and is considered the archetype of the zither and dulcimer; the harp, virginal, harpsichord and clavichord were also inspired by ...

, Saz, Floghera

The floghera ( el, φλογέρα, ) is a type of flute used in Greek folk music. It is a simple end-blown bamboo flute without a fipple, which is played by directing a narrow air stream against its sharp, open upper end. It typically has seven fin ...

, Pithkiavli, Kaval

The kaval is a chromatic end-blown flute traditionally played throughout the Balkans (in Albania, Romania, Bulgaria, Southern Serbia, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Northern Greece, and elsewhere) and Anatolia (including Turkey and Armenia). The ka ...

i, Seistron, Epigonion

The epigonion ( el, ἐπιγόνιον) was an ancient stringed instrument, possibly a Greek harp mentioned in Athenaeus (183 AD), probably a psaltery.

Description

The epigonion was invented, or at least introduced into Greece, by Epigonus of ...

(the ancestor of the Santouri), Varviton (the ancestor of the Oud and a variation of the Kithara), Crotala, Bowed Tambouras (similar to Byzantine Lyra

The Byzantine lyra or lira ( gr, λύρα) was a medieval bowed string musical instrument in the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire. In its popular form, the lyra was a pear-shaped instrument with three to five strings, held upright and played by ...

), Šargija

thumb

The ''šargija'' ( sh, šargija, шаргија; sq, sharki or sharkia), anglicized as ''shargia'', is a plucked, fretted long necked lute used in the folk music of various Balkan countries, including Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Croat ...

, Monochord

A monochord, also known as sonometer (see below), is an ancient musical and scientific laboratory instrument, involving one (mono-) string ( chord). The term ''monochord'' is sometimes used as the class-name for any musical stringed instrument h ...

, Sambuca

Sambuca () is an Italian anise-flavoured, usually colourless, liqueur. Its most common variety is often referred to as ''white sambuca'' to differentiate it from other varieties that are deep blue (''black sambuca'') or bright red (''red sambuc ...

, Rhoptron A rhoptron (( el, ρόπτρον), plural: rhoptra) was a buzzing drum used in Ancient Greece associated with the Corybantes. According to Plutarch, it made a frightening sound, resembling a mix of animal noises and lightning, and was used by the Pa ...

, Koudounia The Koudounia ( el, κουδούνια), are bell-like percussion instruments. Most often, they are made from copper and upon playing (that is, hitting them with a stick) they give out a special ringing sound. Originally the koudounia had been used ...

, perhaps the Lavta

The lavta is a plucked string music instrument from Istanbul.

Description

The Lavta has a small body made of many ribs made using carvel bending technique. Its appearance is somewhat like a small (Turkish) oud - the strings are made from gut l ...

and other instruments used before the 4th Crusade that are no longer played today. These instruments are unknown at this time.

In 2021, archaeologists discovered a flute with six holes dated back to the 4th and 5th centuries AD, in the Zerzevan Castle.

Acclamations at the court and the ceremonial book

Secular music existed and accompanied every aspect of life in the empire, including dramatic productions, pantomime, ballets, banquets, political and pagan festivals, Olympic games, and all ceremonies of the imperial court. It was, however, regarded with contempt, and was frequently denounced as profane and lascivious by some Church Fathers.

Another genre that lies between liturgical chant and court ceremonial are the so-called polychronia (πολυχρονία) and acclamations (ἀκτολογία). The acclamations were sung to announce the entrance of the Emperor during representative receptions at the court, into the hippodrome or into the cathedral. They can be different from the polychronia, ritual prayers or ektenies for present political rulers and are usually answered by a choir with formulas such as "Lord protect" (κύριε σῶσον) or "Lord have mercy on us/them" (κύριε ἐλέησον). The documented polychronia in books of the cathedral rite allow a geographical and a chronological classification of the manuscript and they are still used during ektenies of the divine liturgies of national Orthodox ceremonies today. The

Another genre that lies between liturgical chant and court ceremonial are the so-called polychronia (πολυχρονία) and acclamations (ἀκτολογία). The acclamations were sung to announce the entrance of the Emperor during representative receptions at the court, into the hippodrome or into the cathedral. They can be different from the polychronia, ritual prayers or ektenies for present political rulers and are usually answered by a choir with formulas such as "Lord protect" (κύριε σῶσον) or "Lord have mercy on us/them" (κύριε ἐλέησον). The documented polychronia in books of the cathedral rite allow a geographical and a chronological classification of the manuscript and they are still used during ektenies of the divine liturgies of national Orthodox ceremonies today. The hippodrome

The hippodrome ( el, ἱππόδρομος) was an ancient Greek stadium for horse racing and chariot racing. The name is derived from the Greek words ''hippos'' (ἵππος; "horse") and ''dromos'' (δρόμος; "course"). The term is used i ...

was used for a traditional feast called Lupercalia

Lupercalia was a pastoral festival of Ancient Rome observed annually on February 15 to purify the city, promoting health and fertility. Lupercalia was also known as ''dies Februatus'', after the purification instruments called ''februa'', the b ...

(15 February), and on this occasion the following acclamation was celebrated:

The main source about court ceremonies is an incomplete compilation in a 10th-century manuscript that organised parts of a treatise Περὶ τῆς Βασιλείου Τάξεως ("On imperial ceremonies") ascribed to Emperor Constantine VII, but in fact compiled by different authors who contributed with additional ceremonies of their period. In its incomplete form chapter 1–37 of book I describe processions and ceremonies on religious festivals (many lesser ones, but especially great feasts such as the Elevation of the Cross,

The main source about court ceremonies is an incomplete compilation in a 10th-century manuscript that organised parts of a treatise Περὶ τῆς Βασιλείου Τάξεως ("On imperial ceremonies") ascribed to Emperor Constantine VII, but in fact compiled by different authors who contributed with additional ceremonies of their period. In its incomplete form chapter 1–37 of book I describe processions and ceremonies on religious festivals (many lesser ones, but especially great feasts such as the Elevation of the Cross, Christmas

Christmas is an annual festival commemorating Nativity of Jesus, the birth of Jesus, Jesus Christ, observed primarily on December 25 as a religious and cultural celebration among billions of people Observance of Christmas by country, around t ...

, Theophany

Theophany (from Ancient Greek , meaning "appearance of a deity") is a personal encounter with a deity, that is an event where the manifestation of a deity occurs in an observable way. Specifically, it "refers to the temporal and spatial manifest ...

, Palm Sunday

Palm Sunday is a Christian moveable feast that falls on the Sunday before Easter. The feast commemorates Christ's triumphal entry into Jerusalem, an event mentioned in each of the four canonical Gospels. Palm Sunday marks the first day of Holy ...

, Good Friday

Good Friday is a Christian holiday commemorating the crucifixion of Jesus and his death at Calvary. It is observed during Holy Week as part of the Paschal Triduum. It is also known as Holy Friday, Great Friday, Great and Holy Friday (also Hol ...

, Easter

Easter,Traditional names for the feast in English are "Easter Day", as in the '' Book of Common Prayer''; "Easter Sunday", used by James Ussher''The Whole Works of the Most Rev. James Ussher, Volume 4'') and Samuel Pepys''The Diary of Samuel ...

and Ascension Day

The Solemnity of the Ascension of Jesus Christ, also called Ascension Day, Ascension Thursday, or sometimes Holy Thursday, commemorates the Christian belief of the bodily Ascension of Jesus into heaven. It is one of the ecumenical (i.e., shared b ...

and feasts of saints including St Demetrius

Saint Demetrius (or Demetrios) of Thessalonica ( el, Ἅγιος Δημήτριος τῆς Θεσσαλονίκης, (); bg, Димитър Солунски (); mk, Свети Димитрија Солунски (); ro, Sfântul Dumitru; sr ...

, St Basil

Basil of Caesarea, also called Saint Basil the Great ( grc, Ἅγιος Βασίλειος ὁ Μέγας, ''Hágios Basíleios ho Mégas''; cop, Ⲡⲓⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ Ⲃⲁⲥⲓⲗⲓⲟⲥ; 330 – January 1 or 2, 379), was a bishop of Cae ...

etc. often extended over many days), while chapter 38–83 describe secular ceremonies or rites of passage such as coronations, weddings, births, funerals, or the celebration of war triumphs. For the celebration of Theophany the protocol begins to mention several stichera

A sticheron (Greek: "set in verses"; plural: stichera; Greek: ) is a hymn of a particular genre sung during the daily evening (Hesperinos/Vespers) and morning ( Orthros) offices, and some other services, of the Eastern Orthodox and Byzantine Cat ...

and their echoi (ch. 3) and who had to sing them:

These protocols gave rules for imperial progresses to and from certain churches at Constantinople and the imperial palace, with fixed stations and rules for ritual actions and acclamations from specified participants (the text of acclamations and processional troparia or kontakia, but also heirmoi are mentioned), among them also ministers, senate members, leaders of the "Blues" (Venetoi) and the "Greens" (Prasinoi)—chariot teams during the hippodrome's horse races. They had an important role during court ceremonies. The following chapters (84–95) are taken from a 6th-century manual by Peter the Patrician. They rather describe administrative ceremonies such as the appointment of certain functionaries (ch. 84,85), investitures of certain offices (86), the reception of ambassadors and the proclamation of the Western Emperor (87,88), the reception of Persian ambassadors (89,90), Anagorevseis of certain Emperors (91–96), the appointment of the senate's ''proedros'' (97). The "palace order" did not only prescribe the way of movements (symbolic or real) including on foot, mounted, by boat, but also the costumes of the celebrants and who has to perform certain acclamations. The emperor often plays the role of Christ and the imperial palace is chosen for religious rituals, so that the ceremonial book brings the sacred and the profane together. Book II seems to be less normative and was obviously not compiled from older sources like book I, which often mentioned outdated imperial offices and ceremonies, it rather describes particular ceremonies as they had been celebrated during particular imperial receptions during the Macedonian renaissance.

The Desert Fathers and urban monasticism

Two concepts must be understood to appreciate fully the function of music in Byzantine worship and they were related to a new form of urban monasticism, which even formed the representative cathedral rites of the imperial ages, which had to baptise many catechumens.

The first, which retained currency in Greek theological and mystical speculation until the dissolution of the empire, was the belief in the

Two concepts must be understood to appreciate fully the function of music in Byzantine worship and they were related to a new form of urban monasticism, which even formed the representative cathedral rites of the imperial ages, which had to baptise many catechumens.

The first, which retained currency in Greek theological and mystical speculation until the dissolution of the empire, was the belief in the angel

In various theistic religious traditions an angel is a supernatural spiritual being who serves God.

Abrahamic religions often depict angels as benevolent celestial intermediaries between God (or Heaven) and humanity. Other roles include ...

ic transmission of sacred chant: the assumption that the early Church united men in the prayer of the angelic choirs. It was partly based on the Hebrew fundament of Christian worship, but in the particular reception of St. Basil of Caesarea

Basil of Caesarea, also called Saint Basil the Great ( grc, Ἅγιος Βασίλειος ὁ Μέγας, ''Hágios Basíleios ho Mégas''; cop, Ⲡⲓⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ Ⲃⲁⲥⲓⲗⲓⲟⲥ; 330 – January 1 or 2, 379), was a bishop of Ca ...

's divine liturgy. John Chrysostom

John Chrysostom (; gr, Ἰωάννης ὁ Χρυσόστομος; 14 September 407) was an important Early Church Father who served as archbishop of Constantinople. He is known for his homilies, preaching and public speaking, his denunciat ...

, since 397 Archbishop of Constantinople, abridged the long formula of Basil's divine liturgy for the local cathedral rite.

The notion of angelic chant is certainly older than the Apocalypse

Apocalypse () is a literary genre in which a supernatural being reveals cosmic mysteries or the future to a human intermediary. The means of mediation include dreams, visions and heavenly journeys, and they typically feature symbolic imager ...

account (Revelation

In religion and theology, revelation is the revealing or disclosing of some form of truth or knowledge through communication with a deity or other supernatural entity or entities.

Background

Inspiration – such as that bestowed by God on the ...

4:8–11), for the musical function of angels as conceived in the Old Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

is brought out clearly by Isaiah

Isaiah ( or ; he, , ''Yəšaʿyāhū'', "God is Salvation"), also known as Isaias, was the 8th-century BC Israelite prophet after whom the Book of Isaiah is named.

Within the text of the Book of Isaiah, Isaiah himself is referred to as "the ...

(6:1–4) and Ezekiel

Ezekiel (; he, יְחֶזְקֵאל ''Yəḥezqēʾl'' ; in the Septuagint written in grc-koi, Ἰεζεκιήλ ) is the central protagonist of the Book of Ezekiel in the Hebrew Bible.

In Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, Ezekiel is acknow ...

(3:12). Most significant in the fact, outlined in Exodus

Exodus or the Exodus may refer to:

Religion

* Book of Exodus, second book of the Hebrew Torah and the Christian Bible

* The Exodus, the biblical story of the migration of the ancient Israelites from Egypt into Canaan

Historical events

* Ex ...

25, that the pattern for the earthly worship of Israel was derived from heaven. The allusion is perpetuated in the writings of the early Fathers, such as Clement of Rome

Pope Clement I ( la, Clemens Romanus; Greek: grc, Κλήμης Ῥώμης, Klēmēs Rōmēs) ( – 99 AD) was bishop of Rome in the late first century AD. He is listed by Irenaeus and Tertullian as the bishop of Rome, holding office from 88 AD t ...

, Justin Martyr

Justin Martyr ( el, Ἰουστῖνος ὁ μάρτυς, Ioustinos ho martys; c. AD 100 – c. AD 165), also known as Justin the Philosopher, was an early Christian apologist and philosopher.

Most of his works are lost, but two apologies and ...

, Ignatius of Antioch

Ignatius of Antioch (; Greek: Ἰγνάτιος Ἀντιοχείας, ''Ignátios Antiokheías''; died c. 108/140 AD), also known as Ignatius Theophorus (, ''Ignátios ho Theophóros'', lit. "the God-bearing"), was an early Christian writer ...

, Athenagoras of Athens

Athenagoras (; grc-gre, Ἀθηναγόρας ὁ Ἀθηναῖος; c. 133 – c. 190 AD) was a Father of the Church, an Ante-Nicene Christian apologist who lived during the second half of the 2nd century of whom little is known for certain, ...

, John Chrysostom and Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite

Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (or Dionysius the Pseudo-Areopagite) was a Greek author, Christian theologian and Neoplatonic philosopher of the late 5th to early 6th century, who wrote a set of works known as the ''Corpus Areopagiticum'' or ...

. It receives acknowledgement later in the liturgical treatises of Nicolas Kavasilas and Symeon of Thessaloniki.

The second, less permanent, concept was that of koinonia

() is a transliterated form of the Koine Greek, Greek word , which refers to concepts such as fellowship, joint participation, the share which one has in anything, a gift jointly contributed, a collection, a contribution. It identifies the ideal ...

or "communion". This was less permanent because, after the fourth century, when it was analyzed and integrated into a theological system, the bond and "oneness" that united the clergy and the faithful in liturgical worship was less potent. It is, however, one of the key ideas for understanding a number of realities for which we now have different names. With regard to musical performance, this concept of koinonia may be applied to the primitive use of the word choros. It referred, not to a separate group within the congregation entrusted with musical responsibilities, but to the congregation as a whole. St. Ignatius wrote to the Church in Ephesus in the following way:

You must every man of you join in a choir so that being harmonious and in concord and taking the keynote of God in unison, you may sing with one voice through Jesus Christ to the Father, so that He may hear you and through your good deeds recognize that you are parts of His Son.

A marked feature of liturgical ceremony was the active part taken by the people in its performance, particularly in the recitation or chanting of hymns, responses and psalms. The terms choros, koinonia and ekklesia were used synonymously in the early Byzantine Church. In Psalms

The Book of Psalms ( or ; he, תְּהִלִּים, , lit. "praises"), also known as the Psalms, or the Psalter, is the first book of the ("Writings"), the third section of the Tanakh, and a book of the Old Testament. The title is derived ...

149 and 150, the Septuagint

The Greek Old Testament, or Septuagint (, ; from the la, septuaginta, lit=seventy; often abbreviated ''70''; in Roman numerals, LXX), is the earliest extant Greek translation of books from the Hebrew Bible. It includes several books beyond th ...

translated the Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

word ''machol'' (dance) by the Greek word ''choros'' el, χορός. As a result, the early Church borrowed this word from classical antiquity as a designation for the congregation, at worship and in song in heaven and on earth both.

Concerning the practice of psalm recitation, the recitation by a congregation of educated chanters is already testified by the soloistic recitation of abridged psalms by the end of the 4th century. Later it was called prokeimenon

In the liturgical practice of the Orthodox Church and Byzantine Rite, a prokeimenon (Greek , plural ; sometimes /; lit. 'that which precedes') is a psalm or canticle refrain sung responsorially at certain specified points of the Divine Liturgy or ...

. Hence, there was an early practice of simple psalmody, which was used for the recitation of canticles and the psalter, and usually Byzantine psalters have the 15 canticles in an appendix, but the simple psalmody itself was not notated before the 13th century, in dialogue or '' papadikai'' treatises preceding the book sticheraria. Later books, like the ''akolouthiai'' and some ''psaltika'', also contain the elaborated psalmody, when a protopsaltes recited just one or two psalm verses. Between the recited psalms and canticles troparia were recited according to the same more or less elaborated psalmody. This context relates antiphonal chant genres including antiphona (kind of introit

The Introit (from Latin: ''introitus'', "entrance") is part of the opening of the liturgy, liturgical celebration of the Eucharist for many Christian denominations. In its most complete version, it consists of an antiphon, Psalms, psalm verse and ' ...

s), trisagion

The ''Trisagion'' ( el, Τρισάγιον; 'Thrice Holy'), sometimes called by its opening line ''Agios O Theos'', is a standard hymn of the Divine Liturgy in most of the Eastern Orthodox, Western Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Eastern Cathol ...

and its substitutes, prokeimenon

In the liturgical practice of the Orthodox Church and Byzantine Rite, a prokeimenon (Greek , plural ; sometimes /; lit. 'that which precedes') is a psalm or canticle refrain sung responsorially at certain specified points of the Divine Liturgy or ...

, allelouiarion, the later cherubikon

The Cherubikon ( Greek: χερουβικόν) is the usual Cherubic Hymn ( Greek: χερουβικὸς ὕμνος, Church Slavonic ) sung at the Great Entrance of the Byzantine liturgy.

History

Origin

The cherubikon was added as a tropa ...

and its substitutes, the koinonikon cycles as they were created during the 9th century. In most of the cases they were simply troparia

A troparion (Greek , plural: , ; Georgian: , ; Church Slavonic: , ) in Byzantine music and in the religious music of Eastern Orthodox Christianity is a short hymn of one stanza, or organised in more complex forms as series of stanzas.

The wi ...

and their repetitions or segments were given by the antiphonon, whether it was sung or not, its three sections of the psalmodic recitation were separated by the troparion.

The recitation of the biblical odes

The fashion in all cathedral rites of the Mediterranean was a new emphasis on the psalter. In older ceremonies before Christianity became the religion of empires, the recitation of the biblical odes (mainly taken from the Old Testament) was much more important. They did not disappear in certain cathedral rites such as the Milanese and the Constantinopolitan rite.

Before long, however, a clericalizing tendency soon began to manifest itself in linguistic usage, particularly after the

The fashion in all cathedral rites of the Mediterranean was a new emphasis on the psalter. In older ceremonies before Christianity became the religion of empires, the recitation of the biblical odes (mainly taken from the Old Testament) was much more important. They did not disappear in certain cathedral rites such as the Milanese and the Constantinopolitan rite.

Before long, however, a clericalizing tendency soon began to manifest itself in linguistic usage, particularly after the Council of Laodicea

The Council of Laodicea was a regional Christian synod of approximately thirty clerics from Asia Minor which assembled about 363–364 in Laodicea, Phrygia Pacatiana.

Historical context

The council took place soon after the conclusion of the w ...

, whose fifteenth Canon

Canon or Canons may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Canon (fiction), the conceptual material accepted as official in a fictional universe by its fan base

* Literary canon, an accepted body of works considered as high culture

** Western ca ...

permitted only the canonical '' psaltai'', "chanters:", to sing at the services. The word choros came to refer to the special priestly function in the liturgy – just as, architecturally speaking, the choir became a reserved area near the sanctuary—and choros eventually became the equivalent of the word kleros (the pulpits of two or even five choirs).

The nine canticles or odes according to the psalter were:

* (1) The Song of the sea

The Song of the Sea ( he, שירת הים, ''Shirat HaYam'', also known as ''Az Yashir Moshe'' and Song of Moses, or ''Mi Chamocha'') is a poem that appears in the Book of Exodus of the Hebrew Bible, at . It is followed in verses 20 and 21 by a ...

(Exodus 15:1–19);

* (2) The Song of Moses

The Song of Moses is the name sometimes given to the poem which appears in Deuteronomy of the Hebrew Bible, which according to the Bible was delivered just prior to Moses' death on Mount Nebo. Sometimes the Song is referred to as Deuteronomy 32 ...

(Deuteronomy 32:1–43);

* (3) – (6) The prayers of Hannah, Habakkuk, Isaiah, Jonah (1 Kings Samuel2:1–10; Habakkuk 3:1–19; Isaiah 26:9–20; Jonah 2:3–10);

* (7) – (8) The Prayer of Azariah and Song of the Three Holy Children

The Prayer of Azariah and Song of the Three Holy Children, abbreviated ''Pr Azar'', is a passage which appears after Daniel 3:23 in some translations of the Bible, including the ancient Greek Septuagint translation.

The passage is accepted by so ...

(Apoc. Daniel 3:26–56 and 3:57–88);

* (9) The Magnificat

The Magnificat (Latin for "y soul

Y, or y, is the twenty-fifth and penultimate letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. According to some authorities, it is the sixth (or sevent ...

magnifies he Lord

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

) is a canticle, also known as the Song of Mary, the Canticle of Mary and, in the Eastern Christianity, Byzantine tradition, the Ode of the Theotokos (). It is traditionally incorporated ...

and the Benedictus

Benedictus may refer to:

Music

* Benedictus (Song of Zechariah), ''Benedictus'' (''Song of Zechariah''), the canticle sung at Lauds, also called the Canticle of Zachary

* The second part of the Sanctus, part of the Eucharistic prayer

* Benedictus ...

(Luke 1:46–55 and 68–79).

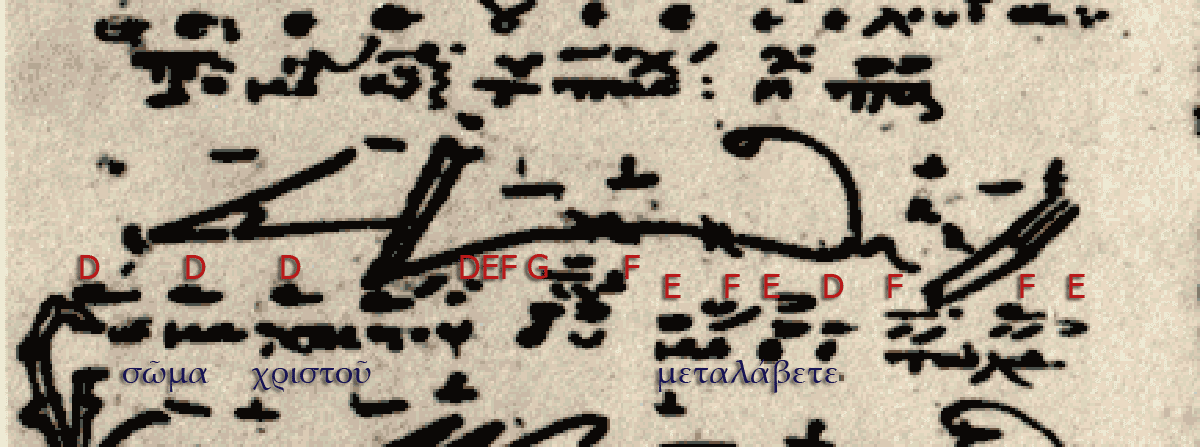

and in Constantinople they were combined in pairs against this canonical order:

* Ps. 17 with troparia Ἀλληλούϊα and Μνήσθητί μου, κύριε.

* (1) with troparion Tῷ κυρίῳ αἴσωμεν, ἐνδόξως γὰρ δεδόξασται.

* (2) with troparion Δόξα σοι, ὁ θεός. (Deut. 32:1–14) Φύλαξόν με, κύριε. (Deut. 32:15–21) Δίκαιος εἶ, κύριε, (Deut. 32:22–38) Δόξα σοι, δόξα σοι. (Deut. 32:39–43) Εἰσάκουσόν μου, κύριε. (3)

* (4) & (6) with troparion Οἰκτείρησόν με, κύριε.

* (3) & (9a) with troparion Ἐλέησόν με, κύριε.

* (5) & Mannaseh (apokr. 2 Chr 33) with troparion Ἰλάσθητί μοι, κύριε.

* (7) which has a refrain in itself.

The troparion

The common term for a short hymn of one stanza, or one of a series of stanzas, is troparion

A troparion (Greek , plural: , ; Georgian: , ; Church Slavonic: , ) in Byzantine music and in the religious music of Eastern Orthodox Christianity is a short hymn of one stanza, or organised in more complex forms as series of stanzas.

The wi ...

. As a refrain interpolated between psalm verses it had the same function as the antiphon

An antiphon ( Greek ἀντίφωνον, ἀντί "opposite" and φωνή "voice") is a short chant in Christian ritual, sung as a refrain. The texts of antiphons are the Psalms. Their form was favored by St Ambrose and they feature prominentl ...

in Western plainchant. The simplest troparion was probably "allelouia", and similar to troparia like the trisagion

The ''Trisagion'' ( el, Τρισάγιον; 'Thrice Holy'), sometimes called by its opening line ''Agios O Theos'', is a standard hymn of the Divine Liturgy in most of the Eastern Orthodox, Western Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Eastern Cathol ...

or the cherubikon

The Cherubikon ( Greek: χερουβικόν) is the usual Cherubic Hymn ( Greek: χερουβικὸς ὕμνος, Church Slavonic ) sung at the Great Entrance of the Byzantine liturgy.

History

Origin

The cherubikon was added as a tropa ...

or the koinonika a lot of troparia became a chant genre of their own.

A famous example, whose existence is attested as early as the 4th century, is the

A famous example, whose existence is attested as early as the 4th century, is the Easter

Easter,Traditional names for the feast in English are "Easter Day", as in the '' Book of Common Prayer''; "Easter Sunday", used by James Ussher''The Whole Works of the Most Rev. James Ussher, Volume 4'') and Samuel Pepys''The Diary of Samuel ...

Vespers

Vespers is a service of evening prayer, one of the canonical hours in Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Catholic Church, Catholic (both Latin liturgical rites, Latin and Eastern Catholic Churches, Eastern), Lutheranism, Lutheran, and Anglican ...

hymn, ''Phos Hilaron

''Phos Hilaron'' ( grc-x-koine, , translit=''Fόs Ilarόn'') is an ancient Christian hymn originally written in Koine Greek. Often referred to in the Western Church by its Latin title ''Lumen Hilare'', it has been translated into English as ''O Gl ...

'' ("O Resplendent Light"). Perhaps the earliest set of troparia of known authorship are those of the monk

A monk (, from el, μοναχός, ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a person who practices religious asceticism by monastic living, either alone or with any number of other monks. A monk may be a person who decides to dedica ...

Auxentios (first half of the 5th century), attested in his biography but not preserved in any later Byzantine order of service. Another, ''O Monogenes Yios ''Only-Begotten Son'' ( grc, Ὁ Μονογενὴς Υἱὸς, Church Slavonic: Единородный Сыне, Ukrainian: Єдинородний Сине, Old Armenian: Միածին Վորդի), sometimes called "Justinian's Hymn", the "Anthem o ...

'' ("Only Begotten Son"), ascribed to the emperor Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

(527–565), followed the doxology of the second antiphonon at the beginning of the Divine Liturgy

Divine Liturgy ( grc-gre, Θεία Λειτουργία, Theia Leitourgia) or Holy Liturgy is the Eucharistic service of the Byzantine Rite, developed from the Antiochene Rite of Christian liturgy which is that of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of C ...

.

Romanos the Melodist, the kontakion, and the Hagia Sophia

The development of large scale hymnographic forms begins in the fifth century with the rise of the

The development of large scale hymnographic forms begins in the fifth century with the rise of the kontakion

The kontakion (Greek , plural , ''kontakia'') is a form of hymn performed in the Orthodox and the Eastern Catholic liturgical traditions.

The kontakion originated in the Byzantine Empire around the 6th century and is closely associated with Sain ...

, a long and elaborate metrical sermon, reputedly of Syriac origin, which finds its acme in the work of St. Romanos the Melodist

Romanos the Melodist (; late 5th-century — after 555) was a Byzantine hymnographer and composer, who is a central early figure in the history of Byzantine music. Called "the Pindar of rhythmic poetry", he flourished during the sixth century ...

(6th century). This dramatic homily which could treat various subjects, theological and hagiographical ones as well as imperial propaganda, comprises some 20 to 30 stanzas (oikoi "houses") and was sung in a rather simple style with emphasise on the understanding of the recent texts. The earliest notated versions in Slavic ''kondakar's'' (12th century) and Greek ''kontakaria-psaltika'' (13th century), however, are in a more elaborate style (also rubrified Idiomelon, idiomela), and were probably sung since the ninth century, when ''kontakia'' were reduced to the ''prooimion'' (introductory verse) and first ''oikos'' (stanza). Romanos' own recitation of all the numerous ''oikoi'' must have been much simpler, but the most interesting question of the genre are the different functions that ''kontakia'' once had. Romanos' original melodies were not delivered by notated sources dating back to the 6th century, the earliest notated source is the Tipografsky Ustav written about 1100. Its gestic notation was different from Middle Byzantine notation used in Italian and Athonite Kontakaria of the 13th century, where the gestic signs (cheironomiai) became integrated as "great signs". During the period of psaltic art (14th and 15th centuries), the interest of kalophonic elaboration was focussed on one particular kontakion which was still celebrated: the Akathist hymn. An exception was John Kladas who contributed also with kalophonic settings of other kontakia of the repertoire.

Some of them had a clear liturgical assignation, others not, so that they can only be understood from the background of the later book of ceremonies. Some of Romanos creations can be even regarded as political propaganda in connection with the new and very fast reconstruction of the famous Hagia Sophia by Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles. A quarter of Constantinople had been burnt down during a Nika riots, civil war. Justinian had ordered a massacre at the hippodrome

The hippodrome ( el, ἱππόδρομος) was an ancient Greek stadium for horse racing and chariot racing. The name is derived from the Greek words ''hippos'' (ἵππος; "horse") and ''dromos'' (δρόμος; "course"). The term is used i ...

, because his imperial antagonists who were affiliated to the former dynasty, had been organised as a chariot team. Thus, he had place for the creation of a huge park with a new cathedral in it, which was larger than any church built before as Hagia Sophia. He needed a kind of mass propaganda to justify the imperial violence against the public. In the kontakion "On earthquakes and conflagration" (H. 54), Romanos interpreted the Nika riot as a divine punishment, which followed in 532 earlier ones including earthquakes (526–529) and a famine (530):

According to Johannes Koder the kontakion was celebrated the first time during Lenten period in 537, about ten months before the official inauguration of the new built Hagia Sophia on 27 December.

Changes in architecture and liturgy, and the introduction of the cherubikon

During the second half of the sixth century, there was a change in Byzantine architecture, Byzantine sacred architecture, because the altar used for the preparation of the eucharist had been removed from the bema. It was placed in a separated room called "Prothesis (altar), prothesis" (πρόθεσις). The separation of the prothesis where the bread was consecrated during a separated service called Liturgy of Preparation, proskomide, required a procession of the gifts at the beginning of the second eucharist part of the divine liturgy. The troparion "Οἱ τὰ χερουβεὶμ", which was sung during the procession, was often ascribed to Emperor Justin II, but the changes in sacred architecture were definitely traced back to his time by archaeologists. Concerning the Hagia Sophia, which was constructed earlier, the procession was obviously within the church. It seems that the

During the second half of the sixth century, there was a change in Byzantine architecture, Byzantine sacred architecture, because the altar used for the preparation of the eucharist had been removed from the bema. It was placed in a separated room called "Prothesis (altar), prothesis" (πρόθεσις). The separation of the prothesis where the bread was consecrated during a separated service called Liturgy of Preparation, proskomide, required a procession of the gifts at the beginning of the second eucharist part of the divine liturgy. The troparion "Οἱ τὰ χερουβεὶμ", which was sung during the procession, was often ascribed to Emperor Justin II, but the changes in sacred architecture were definitely traced back to his time by archaeologists. Concerning the Hagia Sophia, which was constructed earlier, the procession was obviously within the church. It seems that the cherubikon

The Cherubikon ( Greek: χερουβικόν) is the usual Cherubic Hymn ( Greek: χερουβικὸς ὕμνος, Church Slavonic ) sung at the Great Entrance of the Byzantine liturgy.

History

Origin

The cherubikon was added as a tropa ...

was a prototype of the Western chant genre offertory.

With this change came also the dramaturgy of the three doors in a choir screen before the Bema#Christianity, bema (sanctuary). They were closed and opened during the ceremony. Outside Constantinople these choir or icon screens of marble were later replaced by Iconostasis, iconostaseis. Anthony of Novgorod, Antonin, a Russian monk and pilgrim of Novgorod, described the procession of choirs during Orthros and the divine liturgy, when he visited Constantinople in December 1200:

When they sing Lauds at Hagia Sophia, they sing first in the narthex before the royal doors; then they enter to sing in the middle of the church; then the gates of Paradise are opened and they sing a third time before the altar. On Sundays and feastdays the Patriarch assists at Lauds and at the Liturgy; at this time he blesses the singers from gallery, and ceasing to sing, they proclaim the polychronia; then they begin to sing again as harmoniously and as sweetly as the angels, and they sing in this fashion until the Liturgy. After Lauds they put off their vestments and go out to receive the blessing of the Patriarch; then the preliminary lessons are read in the ambo; when these are over the Liturgy begins, and at the end of the service the chief priest recites the so-called prayer of the ambo within the sanctuary while the second priest recites in the church, beyond the ambo; when they have finished the prayer, both bless the people. Vespers are said in the same fashion, beginning at an early hour.

Monastic reforms in Constantinople and Jerusalem

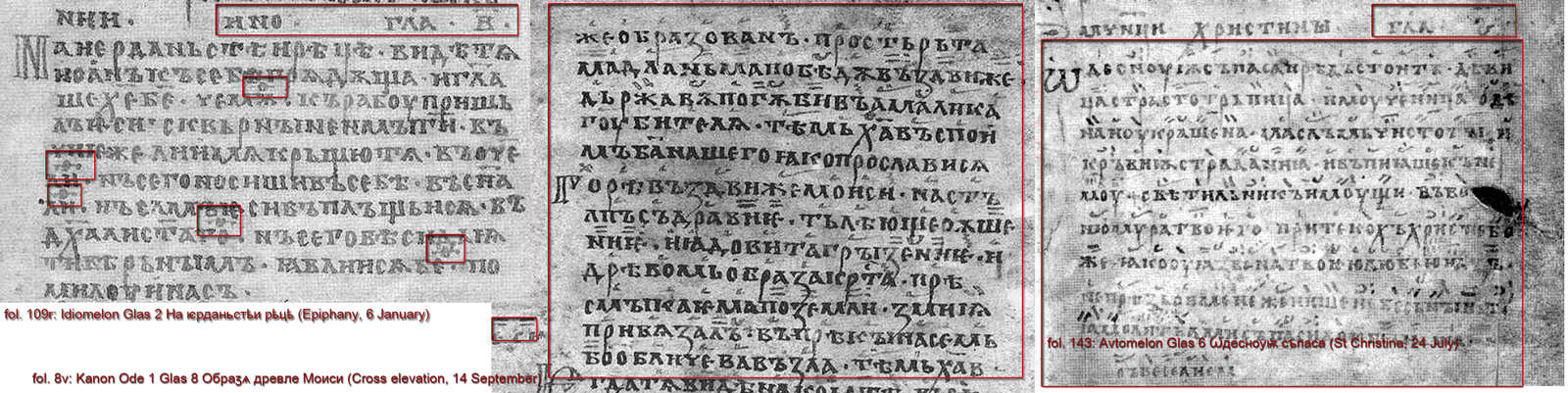

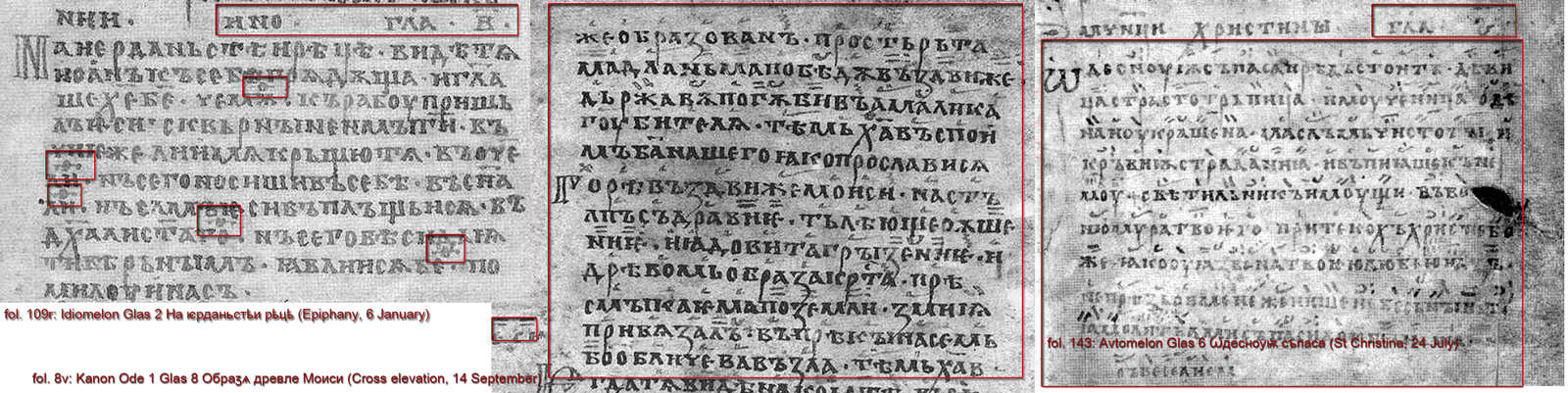

By the end of the seventh century with the Quinisext Council, reform of 692, the kontakion, Romanos' genre was overshadowed by a certain monastic type of Homily, homiletic hymn, the Canon (hymnography), canon and its prominent role it played within the cathedral rite of the Patriarchate of Jerusalem. Essentially, the canon, as it is known since 8th century, is a hymnodic complex composed of nine odes that were originally related, at least in content, to the nine Biblical canticles and to which they were related by means of corresponding poetic allusion or textual quotation (see the #The_recitation_of_the_biblical_odes, section about the biblical odes). Out of the custom of canticle recitation, monastic reformers at Constantinople, Jerusalem and Mount Sinai developed a new homiletic genre whose verses in the complex ode meter were composed over a melodic model: the heirmos.

During the 7th century kanons at the Patriarchate of Jerusalem still consisted of the two or three odes throughout the year cycle, and often combined different echoi. The form common today of nine or eight odes was introduced by composers within the school of Andrew of Crete at Mar Saba. The nine ''odes'' of the ''kanon'' were dissimilar by their metrum. Consequently, an entire ''heirmos'' comprises nine independent melodies (eight, because the second ''ode'' was often omitted outside Lenten period), which are united musically by the same echos and its melos, and sometimes even textually by references to the general theme of the liturgical occasion—especially in ''acrosticha'' composed over a given ''heirmos'', but dedicated to a particular day of the menaion. Until the 11th century, the common book of hymns was the tropologion and it had no other musical notation than a modal signature and combined different hymn genres like troparion

A troparion (Greek , plural: , ; Georgian: , ; Church Slavonic: , ) in Byzantine music and in the religious music of Eastern Orthodox Christianity is a short hymn of one stanza, or organised in more complex forms as series of stanzas.

The wi ...

, sticheron, and Canon (hymnography), canon.

The earliest tropologion was already composed by Severus of Antioch, Paul of Edessa and Ioannes Psaltes at the Patriarchate of Antioch between 512 and 518. Their Octoechos (liturgy), tropologion has only survived in Syriac translation and revised by Jacob of Edessa. The tropologion was continued by Sophronius of Jerusalem, Sophronius, Patriarch of Jerusalem, but especially by Andrew of Crete's contemporary Germanus I of Constantinople, Germanus I, Patriarch of Constantinople who represented as a gifted hymnographer not only an own school, but he became also very eager to realise the purpose of this reform since 705, although its authority was questioned by iconoclast antagonists and only established in 787. After the octoechos reform of the Quinisext Council in 692, monks at Mar Saba continued the hymn project under Andrew's instruction, especially by his most gifted followers John of Damascus and Cosmas of Maiuma, Cosmas of Jerusalem. These various layers of the Hagiopolitan tropologion since the 5th century have mainly survived in a Georgian type of tropologion called "Iadgari" whose oldest copies can be dated back to the 9th century.

Today the second ode is usually omitted (while the great kanon attributed to John of Damascus includes it), but medieval heirmologia rather testify the custom, that the extremely strict spirit of Moses' last prayer was especially recited during Lenten tide, when the number of odes was limited to three odes (triodion

The Triodion ( el, Τριῴδιον, ; cu, Постнаѧ Трїωдь, ; ro, Triodul, sq, Triod/Triodi), also called the Lenten Triodion (, ), is a liturgical book used by the Eastern Orthodox Church. The book contains the propers for th ...

), especially patriarch Germanus I contributed with many own compositions of the second ode. According to Alexandra Nikiforova only two of 64 canons composed by Germanus I are present in the current print editions, but manuscripts have transmitted his hymnographic heritage.

The monastic reform of the Stoudites and their notated chant books

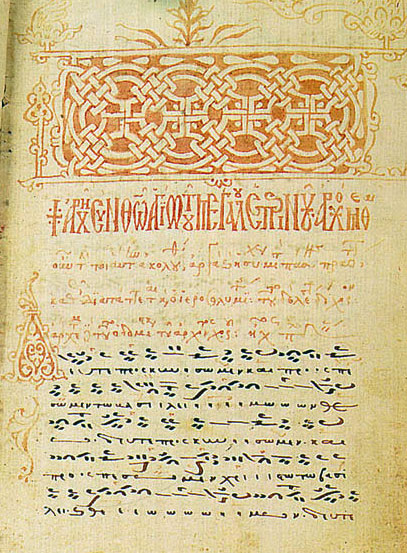

During the 9th-century reforms of the Stoudios Monastery, the reformers favoured Hagiopolitan composers and customs in their new notated chant books heirmologion and

During the 9th-century reforms of the Stoudios Monastery, the reformers favoured Hagiopolitan composers and customs in their new notated chant books heirmologion and sticherarion

A sticheron (Greek: "set in verses"; plural: stichera; Greek: ) is a hymn of a particular genre sung during the daily evening (Hesperinos/Vespers) and morning (Orthros) offices, and some other services, of the Eastern Orthodox and Byzantine Cath ...

, but they also added substantial parts to the tropologion and re-organised the cycle of movable and immovable feasts (especially Lent, the , and its scriptural lessons). The trend is testified by a 9th-century tropologion of the Saint Catherine's Monastery which is dominated by contributions of Jerusalem. Festal stichera, accompanying both the fixed psalms at the beginning and end of Vespers, Hesperinos and the psalmody of the Orthros (the Ainoi) in the Morning Office, exist for all special days of the year, the Sundays and weekdays of Lent, and for the recurrent cycle of eight weeks in the order of the modes beginning with Easter

Easter,Traditional names for the feast in English are "Easter Day", as in the '' Book of Common Prayer''; "Easter Sunday", used by James Ussher''The Whole Works of the Most Rev. James Ussher, Volume 4'') and Samuel Pepys''The Diary of Samuel ...

. Their melodies were originally preserved in the ''tropologion''. During the 10th century two new notated chant books were created at the Stoudios Monastery, which were supposed to replace the tropologion:

# the ''sticherarion

A sticheron (Greek: "set in verses"; plural: stichera; Greek: ) is a hymn of a particular genre sung during the daily evening (Hesperinos/Vespers) and morning (Orthros) offices, and some other services, of the Eastern Orthodox and Byzantine Cath ...

'', consisting of the idiomela in the ''menaion'' (the immoveable cycle between September and August), the ''triodion'' and the ''pentekostarion'' (the moveable cycle around the holy week), and the short version of ''Octoechos (liturgy), octoechos'' (hymns of the Sunday cycle starting with Saturday evening) which sometimes contained a limited number of model troparia (Idiomelon, prosomoia). A rather bulky volume called "great octoechos" or "parakletike" with the weekly cycle appeared first in the middle of the tenth century as a book of its own.

# the ''heirmologion'', which was composed in eight parts for the eight echoi, and further on either according to the canons in liturgical order (KaO) or according to the nine odes of the canon as a subdivision into 9 parts (OdO).

These books were not only provided with musical notation, with respect to the former ''tropologia'' they were also considerably more elaborated and varied as a collection of various local traditions. In practice it meant that only a small part of the repertory was really chosen to be sung during the divine services. Nevertheless, the form ''tropologion'' was used until the 12th century, and many later books which combined octoechos, sticherarion and heirmologion, rather derive from it (especially the usually unnotated Slavonic ''osmoglasnik'' which was often divided in two parts called "pettoglasnik", one for the kyrioi, another for the plagioi echoi).

The old custom can be studied on the basis of the 9th-century tropologion ΜΓ 56+5 from Sinai which was still organised according to the old tropologion beginning with the Christmas and Epiphany cycle (not with 1 September) and without any separation of the movable cycle. The new Studite or post-Studite custom established by the reformers was that each ode consists of an initial troparion, the heirmos, followed by three, four or more troparia from the menaion, which are the exact metrical reproductions of the heirmos (akrostics), thereby allowing the same music to fit all troparia equally well. The combination of Constantinopolitan and Palestine customs must be also understood on the base of the political history.